I was trying to get this out before the new year because I want this to be a quarterly newsletter, but that’s just going to have to start this year. I think it was meant to be, though, since these notes (25 for ‘25) helped me synthesize reading from both recently and long ago, versus an inventory of what I read in 2024, plenty of which was irrelevant or just for me. Happy new year!

As we’re leaving the library, a woman compliments me on having children who read books. It feels a little like being told I’m “such a good dad” —i.e, congratulated for something basic. I’ve also been thinking about the ethics of forcing my love language—a shared literary canon—onto my children and answer the woman in turn:

“I read books, so they have to if they want my full attention.”

We leave her to ponder whether this is a good or bad thing for a parent to say, which is also what I’ve been wondering. Sometimes, my relationship to reading feels too obsessive-compulsive to be fully healthy (especially when it interferes with sleep). My kids seem to know that when I’m unreachable in other ways, they can still count on me to read to them, and some days, reading to them is the most active parenting I do.

I read the second part of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, which is about how kids learn to read. (The first part is about how humans evolved to read and the third part about the neuroscience behind reading disabilities like dyslexia. I have yet to read either of these parts.) The book’s thesis is that there isn’t a specific part of the brain evolved for reading, like there is for early language acquisition. The reading brain has to be built from other parts of the brain, including those involved with everything from pattern recognition to attachment. This reminds me of something Beverly Clearly, a former children’s librarian, wrote in a Ramona book (can’t remember which) about Ramona’s nostalgia for her mother reading her animal stories as a small child and how a desire to return to the warmth of these memories makes her want to read. So there’s an evolutionary benefit, apparently, to books as love.

In February, we’re in DC for what I don’t yet know is my family’s last time gathering together in my childhood home. Joe, the kids, and I stay in a nearby Airbnb. On the bookshelf, I find a copy of The Screwtape Letters, which I read, after everyone has gone to bed, in a neon green living room. Joe told me the book screwed (ha) with him in adolescence, and I want to understand his teenage belief system (Catholicism). I also like books that screw with me, at least in the sense of getting under my skin and hard to shake off.

The Screwtape Letters does that, but probably not the same way it did for teenage Joe. CS Lewis cautions against saying this, but I don’t believe in demons or the devil. It’s Lewis, however, who gets me thinking about hell as someplace internal, which can grow to engulf us if not “nipped in the bud,” which I quoted here recently, and which this year has given me much occasion to think about. That quote isn’t even from The Screwtape Letters but is, for me, what The Screwtape Letters is about. Although not explicitly a WW2 book, it was written then and ends in the trenches of war.

I read Practicing Peace by Pema Chodron who says, “War and peace start in the human heart.” She talks about “hardening and tightening and rigidity of the heart [behind which] there's always fear. But if you touch fear, behind fear, there is a soft spot. And if you touch that soft spot, you find the vast blue sky.” I want to touch the soft spot more this year.

At another formative time in life, I read and loved CS Lewis’ A Grief Observed, which I still think about, particularly this: “All reality is iconoclastic. The earthly beloved . . . incessantly triumphs over your mere idea of her. And you want her to; you want her with all her resistances, all her faults, all her unexpectedness. That is, in her foursquare and independent reality.” At another point he calls this “obstinately real.” While he’s talking about his wife, I think about this most recently when my kids are driving me crazy. It’s good, I tell myself, because it means they’re real.

I want to read more Lewis, and Joe suggests Mere Christianity, claiming it’s very persuasive. Seeing how affected I’ve been by these other Lewis books, I wonder if it will be the thing that makes an irrefutable case for Christianity. In fact, it does the opposite, convincing me that Lewis and I have fundamentally different belief systems. His argument for monotheism makes me realize I’m more of a panentheist or pantheist (not to be confused with polytheist). I don’t think this is necessarily incompatible with Christianity, but according to Lewis, it is.

E and I start reading The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and stop with a few chapters left to go. It comes up again recently when there’s a wardrobe in this beautiful if somewhat extra version of Peter Pan. “We still have to finish that book,” E says of TLW&W, and I’m sure we will eventually. One of my favorite things about books is that they wait for you.

E’s favorite books of the year were the MinaLima Wizard of Oz and graphic novels Swim Team, Parachute Kids, and Allergic. Not a book, but she also loves the storytelling podcast Circle Round, which we listen to nonstop in the car. (Got her a “club” membership for Christmas.) J’s favorite books were the Dory Fantasmagory series and Crowned: Fairy Tales from the Diaspora, both of which she still asks to be read from regularly. I experienced a Proustian jolt of recognition while reading them the Fox books by James Marshall. I have no conscious memory of being read these books yet remember certain details from the pictures like a long lost article of clothing.

We got a little bored by TLW&W, tbh. It reminded me of reading The Faerie Queene in Renaissance Poetry in college and having to write a paper about how the lion represents strength etc. I don’t get the point of this kind of algebraic allegory; I’m not trying to study math. We also read Paradise Lost in that class, though, which made it worth it.

Just looked it up, and CS Lewis actually didn’t consider TLW&W to be an allegory. I’ll keep this in mind when we read the rest. Still, it’s a spiritual battle between good and evil that takes place outside the human mind.

I don’t believe in the devil because it feels too convenient for evil to exist as a separate entity from human beings. This reminds me of Brandon Taylor’s response to the Alice Munro revelations, particularly this part: “There isn’t ‘the art and the artist’ and one does not ‘separate art from artist.’ To my mind, that is a broken moral calculus that confuses rectitude for an honest accounting of how we live in the world. [. . .] The better question is why do you need to feel comfortable in the rightness of the art you engage. Why do you need to create a safe art that has no harmful valences in it? I know why. You know why. Because otherwise, one has to own up to the knife you hold behind you, ready to plunge it into your brother’s back. Otherwise, you have to own up to the commonness and smallness and the very humanness of monstrosity itself.”

Taylor’s was the best response I read in the immediate aftermath of the Munro revelations. Rachel Aviv’s recent essay in the New Yorker is the deeply researched dive I’ve been waiting for, including analyses of many Munro stories, which are the reason I wasn’t totally surprised when the truth came out.

I wrote my college thesis on three stories in Open Secrets, the collection Munro published after learning that her daughter, Andrea Skinner, had been sexually abused as a child by her longterm partner Gerry Fremlin, ultimately choosing to remain with Fremlin and become estranged from Skinner and her children. (According to Skinner, her mother tried to leave Fremlin “nearly every summer,” “but then the drama of leaving would trip the intimacy wire, bringing her back to him with even greater force,” which also reminds me of the titular story of her following collection, “Runaway.”) One of these stories, “Vandals,” is the most clearly inspired by what Munro called “The Subject.” Another was the titular “Open Secrets,” which seems to have been inspired by Munro’s suspicion that Fremlin may have raped and murdered a 12-year-old girl in an unsolved case from 1959 (Aviv reports it’s unlikely Fremlin was involved.)

Why did I choose these stories? I think because I detected a “secret intensity lurking beneath” them, which was not wrong. I still think they should be read, that they have much to teach us. The mistake I made, that many people made, was to assume their “grisly leitmotifs were the product of a saintly lady who was making it all up, out of empathy.”

Why did we assume this? “I know why. You know why.” The categories of saint and monster help us deny “the germs of every human infirmity” we have inside us (Thomas Hardy, quoted by Garth Greenwell in Small Rain and here).

But it’s a good impulse, essential to literature, to separate fiction from autobiography. Still, some writers are granted this license more than others. Aviv’s article illuminates a whole apparatus, including Alice Munro, her family, agents, editors, publishers, and journalists, working together to preserve the image of her as a “saintly lady,” even once the news was public knowledge, an open secret.

I reread some of the earlier Munro stories Aviv references. It doesn’t even feel like rereading since I read most of them during a single year in college and they crowded each other out. At the end of “Dulse,” the narrator has a small confrontation with a man who idolizes Willa Cather. Afterwards she thinks, “What a lovely, durable shelter he had made for himself. He could carry it everywhere and nobody could interfere with it.”

I made a similar shelter from Alice Munro, and it’s almost freeing to lose it. “Now, I can see the moon,” as the haiku goes. She wasn’t out-empathizing any of us. She was a craftsperson, transforming life into gold, as her family called it. Her later stories are a study, Aviv writes, in “how a mind can be almost completely closed to the truth, except for a few small pockets of knowing.”

It feels important to understand how a mind can do this. It’s also the theme of The Zone of Interest, which I wrote about here in spring and which continues to shape my thinking. It kicked off a WW2 reading jag for me, although looking back, I see it was actually The Screwtape Letters that kicked it off.

I read Man’s Search for Meaning and what feels like its spiritual antithesis, Fatelessness. I read Sophie’s Choice, which is riveting and not what I expected. It’s set in post-war Brooklyn and one of the horniest books I’ve read. The infamous choice, which would be impossible to read about for 600 pages, is only revealed toward the end. While a prisoner in Auschwitz, Sophie also reveals she worked as a translator in the home office of Rudolf Hoss, the same commander portrayed in The Zone of Interest. I’m guessing both William Styron and Jonathan Glazer read the memoir Hoss wrote before his execution, since the book and film have some overlapping details.

I try to tell Joe about this connection between Sophie’s Choice and The Zone of Interest, which we watched together, and am interrupted by a child. I try again, but he’s distracted by something to do with work. I tell him I’m sad we no longer read the same books, so he starts reading Sophie’s Choice. I mainly want to see what he thinks about the connections the book makes between the Holocaust and the American South, which I know interests him. Sophie’s Choice is a southern Holocaust novel set in Brooklyn.

Fortunately for Joe, I decide I don’t care if he finishes Sophie’s Choice and would prefer he use his limited time to read Stoner, which I read for the first time in October after hearing people recommend it for fifteen years (books wait for you). I sell it as a perfect novel, all about work. He reads it and agrees. It encompasses both World War I and II and is much shorter than Sophie’s Choice.

I subscribe to our local paper shortly before the election, possibly intuiting the need to overhaul my relationship with news media soon. Although it’s in the name, I somehow don’t register it will come daily. Once it starts, I almost switch to digital, but Joe wants to keep it, and now I’m glad. There are usually local pictures on the front versus, by default, the worst people in the world. But there’s also national and international coverage. I’m trying to quit Wordle and Connections in favor of the crossword here (syndicated from the LA Times) but am still hooked on Wordle, just like they wanted. But this is a plug for your local paper if Bezos hasn’t bought it yet.

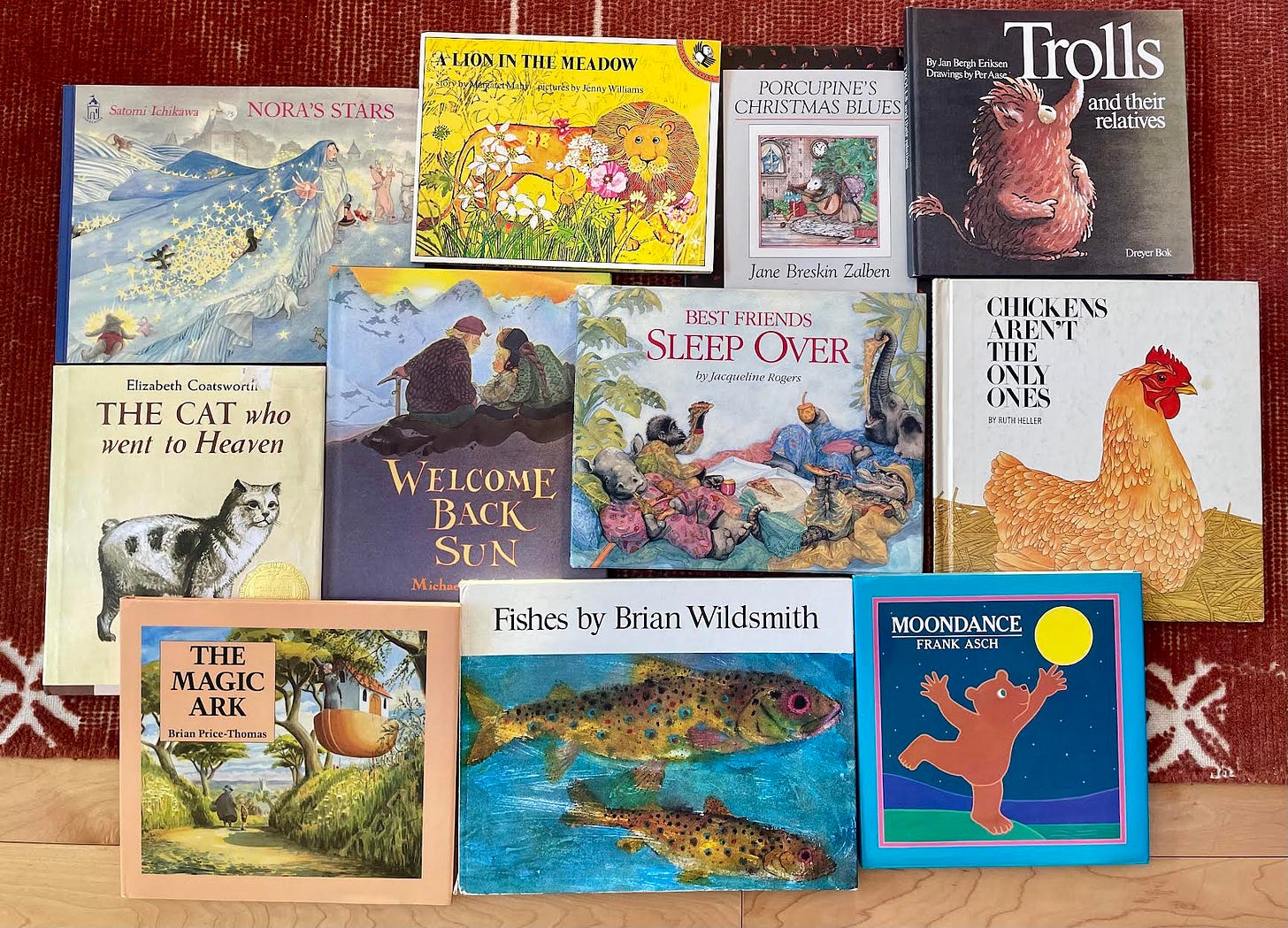

Well, here we are, and I didn’t even get to dementia and how it shaped my family and reading and country. Maybe next time. For now, I’ll just leave a picture of some of the enchanting picture books I’ve found in stashes pristinely preserved by my mother in law, starting around the time Joe was born. She hasn’t spoken a word in years but speaks across time through the many books she collected, which I’m happy to read to the kids on her behalf. Apparently, we shared a love language.

This is very relatable: some days, reading to them is the most active parenting I do.

And now I want to read Proust and The Squid too.

very drawn to 'chicken's aren't the only ones'-- what a mysterious name! also this made me want to read sophie's choice, you said it was horny and i was onboard lol