Leaves & Letters

on anguished literary correspondence

I’ve been reading letters as the leaves fall. I think I associate leaves with letters because of this Rilke poem, “Autumn Day” (sometimes translated as “October Day”), which is one of my faves, particularly the last stanza:

Whoever has no house now, will never have one. Whoever is alone will stay alone, will sit, read, write long letters through the evening, and wander on the boulevards, up and down, restlessly, while the dry leaves are blowing.

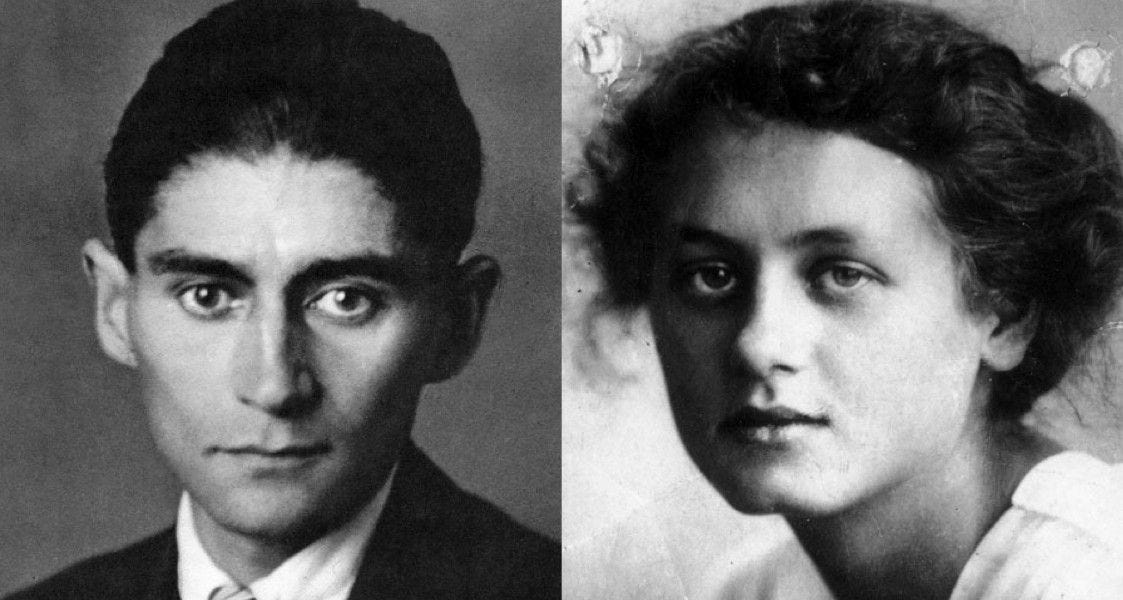

In French, which I studied for a while, the word leaves, feuilles, can also mean papers. I was reminded of this recently while reading one of Kafka’s letters to Milena Jesenska, whom he chides for not sharing her published writing:

"You don’t want to send me your feuilletons, so you obviously don’t trust me to place them properly in the picture I am forming of you. Alright then, I’ll be mad at you on this score, which incidentally is no great misfortune, as things balance out quite well if there is a little anger lurking for you in one corner of my heart."

They were writing to each other in German and Czech, but feuilletons obviously comes from feuilles, although I’m sure there are similar correspondences in other languages, including English (e.g. Leaves of Grass). Anyway, I understand why Milena was reluctant to send Kafka, thirteen years her senior plus Kafka, her feuilletons, but she did, and he wrote back:

“I just read the letter, your essays, again and again, convinced that such prose does not exist merely for its own sake, but serves as a signpost on the road to a human being, a road one keeps following, happier and happier, until arriving at the realization some bright moment that one is not progressing, simply running around inside one’s own labyrinth, only more nervously, more confused than before. But in any case: this was not written by an ordinary writer. After reading it I have almost as much faith in your writing as I do in you yourself.”

Their relationship was comprised almost entirely of letters because Milena was married (albeit to a philanderer), and Kafka was in a tuberculosis sanatorium (drinking lots of milk) and also because he viewed the situation as an opportunity "to put [himself] to the test.” A purity test, I suppose, although the letters did eventually lead to them meeting, thankfully; otherwise I’d find them unbearably depressing. They met two times before Kafka broke off the correspondence, calling it “pure anguish,” although we know from other letters that he continued to think and dream about her until his death four years later, at which point he left her his journals. Milena’s letters to him "were destroyed,” according to Phillip Boehm’s introduction. The passive voice is interesting—was it Kafka who destroyed them?

I have to read Kafka’s letters in small doses because they feel almost too intimate. I find letters even more intimate than diaries, although I like them both (currently also reading Annie Ernaux’s diary of obsessive desire, Getting Lost, and feeling very pleased about her Nobel win). But letters give you something most journals don’t: the presence of another person, often beloved, which ensnares the reader in a sense of urgency, even if the reader is not whom the letter is for. “Letters are above all useful as a means of expressing the ideal self,” writes Elizabeth Hardwick, “and no other method of communication is quite so good for this purpose.” Indeed, I cannot think of another. But I’m a word person.

It’s interesting to think about Elizabeth Hardwick’s ideal self in relation to the letters she wrote Robert Lowell in The Dolphin Letters, which I’m also reading and much faster than Kafka. They’ve hooked me in the manner of a very public literary breakup occurring on social media. They document the dissolution of Hardwick and Lowell’s marriage when he went to England for a fellowship and ended up shacking up with Caroline Blackwood. While doing this, he was also writing to Hardwick, encouraging her to quit her job and uproot their family from New York so they could be with him in England, which ended up being impossible because he was already with Blackwood. Hardwick had to find a new apartment, job, and school for their daughter back in New York, which she did while organizing Lowell’s papers (old letters) for sale. He responded by lifting large chunks of the letters she wrote him during this time and publishing them in his poetry collection The Dolphin, which then won a Pulitzer.

The sum of what Lowell did is almost unfathomably cruel, and in his defense, he was experiencing some pretty severe mania. I don’t know what that’s like, although I do know how painful it is to unwittingly act out unconscious impulses in the real world. “My eyes have seen what my hand did,” wrote Lowell in “Dolphin.” Still, Hardwick protected him from the worst consequences of his actions, particularly the loss of her. She let loose on him a few times, but more letters depict her as kind and transcendent. I wonder if she wrote to him to keep her ideal self alive, if that self was originally forged through their correspondence. Fortunately, she got to go on lots of Maine vacations with her BFF Mary McCarthy, so it wasn’t all bad. She and Lowell eventually reunited (after his marriage to Blackwood collapsed), then she outlived him by thirty years.

I recently got a letter from Substack about why we should stop calling newsletters letters. (Spoiler: it’s money.) It was honestly the kind of document that made me glad I no longer live in San Francisco. Anyway, I just wanted to say that I’m definitely writing letters here and also like receiving them, and letters are wonderful and irreplaceable and often free.