For a couple years1, my kids (now 4 & 6) were enrolled in a very gentle swim class. It met weekly at a nearby gym, which felt like all the commitment we could handle, especially on 20-degree winter days with minutes to get them from snow gear at school to swimsuits in the pool. To reduce anxiety, I signed them up for private lessons (just the two of them), although I’d heard peer pressure was an important part of the process. No thanks. I’d had a bad experience in group lessons when small (my best friend and I were put in different groups when I wouldn’t put my head in the water) and what is parenting if not an attempt to rectify past trauma?

The focus of the gentle swim class was getting comfortable in the water. No skill was considered more important than this, and since my kids spent each class getting comfortable, they did not learn many skills. They announced each class they wouldn’t go underwater yet wore goggles in case water splashed near their eyes. They said no thanks to the chance to retrieve rings off a knee-deep step. They floated with a teacher’s hands under their backs and paddled as she held them. At no point did they fully enter the pool without a teacher holding them, although they were in the shallow end and could have stood if they put their feet down.

My younger child follows her sister’s lead in many things, including this swim class, yet has a troubling lack of fear in other aquatic settings. The first time she went to an aquarium, she started stripping off her clothes, ready to jump in with the stingrays. Last summer, we were at my in-laws’ community pool, and the lifeguard took an unannounced bathroom break. We were getting out, so I’d taken off her puddle jumper, and she was playing on the steps as I talked to another adult in the pool. My older kid interrupted in the way she often does, repeatedly yelling “Mom!” I tried to ignore her until I realized she was telling me her sister was underwater, which was in fact the case. She’d ventured off the steps and was now fully submersed in drowning position. I could see the panic in her eyes as I reached out and pulled her back up. She coughed up water and started crying but was soon recovered.

They wouldn’t stop talking about it, though. E talked about the time J “almost drowned and I didn’t have a little sister to play with anymore.” J now seemed to consider going underwater synonymous with drowning, yet still did things like run into the ocean alone. Outside the comfort swim class, neither would enter a pool without a flotation device, while algorithms fed me stories about how dangerous these devices are, as they give kids false confidence and condition their bodies to take the drowning position (see above).

I asked other parents how their kids learned to swim. A few mentioned Infant Swimming Resources (ISR)2 lessons, of which I’d seen videos online: babies rolling from fully underwater to floating calmly on their backs. My kids are no longer infants, but the classes are for kids 6 months to 6 years. I looked them up and saw they entailed daily 10-minute lessons for 6 weeks. I didn’t want to drive to daily swim classes for 6 weeks. Getting to swim class once a week was already, in my view, triumphant parenting. I ordered pizza to celebrate the victory every time. Was I going to order daily pizzas for 6 weeks?3

Then, in an unplanned move, one of the friends who recommended ISR lessons sold us her house. And now she recommended them again because this house has a pool, and drowning is the leading cause of death in the U.S. for kids 1-4, with backyard pools accounting for over half those deaths. I’d learned from above experience how quickly it could happen (30 seconds), as well as an episode of The Pitt which gave me PTSD. The pool already has a lock and fence, and we supervise the kids in it, but water competency is one of the layers of protection that prevent drowning, and my kids didn’t have it.

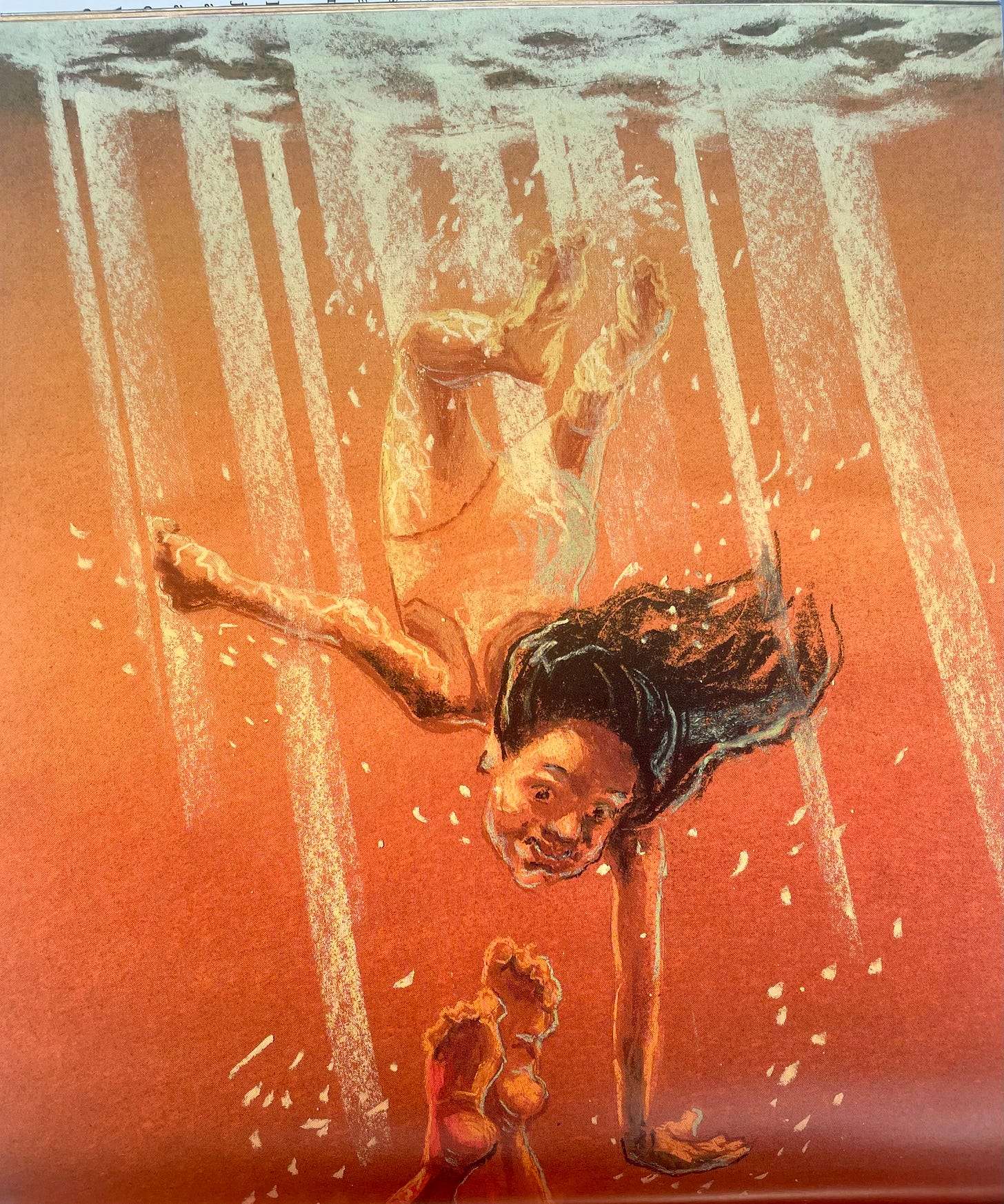

Water competency describes what I want for them, though. I don’t care about perfect strokes, but I want them to know how to move through water and let it hold them (and not drown). I’m a “fish head,” as a friend once put it, entranced with everything underwater. Swimming is the best way I know to escape the limits of our bodies, and I knew once my kids experienced that, they’d love it too. But when I got in the water and tried to persuade them, the magic dried up into stress and anxiety. I wanted it too badly, the worst state of mind for getting them to do something.

I asked if the ISR teacher could teach in our pool, but she was way too booked for that. She had exactly two spots left for summer: 4:30 and 4:40, meaning my kids could still do the day camp I’d signed them up for before I knew we were going to be spending so much time and money4 on this. Lessons were held in the instructor, A.’s parents’ pool: bright blue with a diving board at one end. The first time I saw her, she was teaching a baby like in the videos, rolling them from face down in the water to face up again, while the baby cried and coughed up water. A. was calm, very pregnant, and joined in the pool by three other water competent young kids—her kids, she explained. Goddess, I decided, especially after she said she was running late because of her “other job,” which I later found out was training lifeguards. How many lives has she preemptively saved?

The goal of ISR is to teach little kids how to survive a fall into the water. Babies learn to roll onto their backs and float until help arrives. Kids who can walk learn the “swim-float-swim” sequence: swimming a short distance underwater, floating on their backs to breathe and rest, then repeating until they’ve reached safety. This sequence is used because it’s hard for little kids to lift their heads to breathe while swimming (if you see them try, you’ll notice they often go vertical, the drowning position). Also, they need to know how to hold their breath underwater (not just blow bubbles, like they did in the other swim class). In other words, there would be no escaping going underwater. That’s the first step, since it’s the first thing that happens if you fall in the water.

A 4-year-old I’ll call Z went before us, and A. started by releasing him into the water a few inches from the pool steps. We’d watched her do the same with another 4-year-old, who’d gone under, reoriented, then resurfaced on the steps with a cough and a smile. Z had a different reaction. He resurfaced, gasped, then howled for the next 10 minutes. Through sobs and pool water, he repeatedly screamed, “I only want to do things I’m good at!” (Honestly, same.) His mom watched stoically, which I could tell took effort, that she was a fellow millennial versed in gentle parenting.

Then in was J’s turn. We decided she’d go first because she had less anxiety. She immediately inhaled water then started screaming, too. I blacked out the rest. We’d received extensive guidelines before class, including a directive not to eat for an hour before, and now I saw why (at least until they figure out how to stop gagging). Other instructions, such as dietary restrictions (no apples?) and daily bowel and urine checks, fortunately seemed intended only for younger babies, although they freaked me out when I first read them. (We eat a lot of apples.)

A. took a slower approach with E, likely because I was upfront about her anxiety in the medical forms (every ISR student has to be cleared by a nursing team) and also because she was clearly terrified: silently crying and shaking. Her effort to hold it together showed me how far she’s come from a screaming 4-year-old. A. took an incremental approach, having E put her mouth then nose then whole face in the water. By the end of the first week, she was swimming a short distance underwater to a bar on the side of the pool. She wasn’t enjoying it, but she was doing it, which felt huge

Z, however, was still screaming, which set off a chain reaction since he went before us every day. When it was J’s turn, she ran away into the yard, and I had to chase her down and carry her kicking and screaming back to the pool. I was worried she’d kick A in her pregnant belly. I tried showing up a later, but Z’s screams greeted us each time we arrived. On the last day of the first week, I waited him out in the car, blasting Meghan Trainor (E’s fave) until it was our turn. I wasn’t sure when this would be (A, like most miracle workers, was rarely on schedule) but at some point, I got out and heard nothing but birdsong and figured it was safe. Yet when we got to the pool, Z was still in it—swimming underwater and surfacing with a smile. He’d “broken through” as A. called it. That was when I began to trust the process, a phrase I can’t say anymore without feeling like I’m on a reality show with a sadistic premise.

Because I trust the friend who’d recommended ISR (who’d also said my kids might “not like it” at first), it was only now that I googled and found accounts of people claiming these lessons traumatized their kids and made them hate the water. This didn’t seem to be happening with my kids, especially J who ran straight to the ocean on a trip there the next week, but it did make me wonder if I was doing the right thing. But parenting sometimes requires the deployment of small “traumas” to prevent bigger ones—e.g. shots to prevent deadly diseases, temporary separation to prevent parental burnout, etc.—which was how I was starting to view ISR. It was a practice in sitting with screaming, my least favorite part of parenting, having faith my kids would “break through.”

And E did the next week, back in my in laws’ community pool. Joe had taken off that week for vacation long before I signed up for ISR, so I paid to maintain our spot and packed for a week at the beach, feeling slightly truant. I bribed E with Yoto cards to practice for 10 minutes a day in the pool (J got the same bribe to stop running away at the start of each lesson). On the first day, I stood near the pool steps and coaxed E to swim to me underwater. She did, then realized she loved being underwater. We all do, I think, once we overcome that initial fear, that our bodies retain some memory of life as aquatic creatures—from the womb or millions of years before.

E stayed in the pool for the next couple hours, swimming between me, the steps, and the side, mostly underwater. I got out and took a video in which my voice belies my awe (I’m trying not to jinx it). She swims to the steps, and I say, “Go out and do it again.” A dad in the background of the video turns to look, and I imagine he’s surprised by my authority. I am, at least. Usually, when I record myself talking to the kids, I find myself speaking more gently than I remember feeling. Not here. I’m speaking like a coach to an athlete.

A. is impressed when we return the next week. Now E is ready to float, which she does beautifully, possibly due to all the practice in the gentle swim class (so maybe it did something). She reclines fully in the water, a skill that eludes me after a childhood of chronic ear infections and tympanostomies. Fortunately, my kids don’t seem to have inherited my dysfunctional eustachian tubes.

J breaks through that day, too, after I accompany her into the pool. She swims underwater between A. and me and is soon loving it. She’s less into floating. My mom arrives later that week and practices in the pool with the girls just like she used to with me. At one point, she’s inside with E, and I’m checking the filter for frogs5 and look beside me to find J bicycling vertically underwater. I pull her up and she cries. She’d swum out to me but didn’t have enough breath to go the full way. The float is truly critical.

The next week, E masters rolling from a swim to a float and back again, diligently staying a step head of her sister. J masters it the following week, but still prefers to be underwater, so needs to be watched like a hawk. By the fifth week, they’re both jumping off the diving board then swim-float-swimming to the side of the pool by themselves. We’re in the final week now, and they’ve practiced after tumbling into the water from multiple directions and while fully dressed. Tomorrow they’ll practice in snowsuits, which I still need to unpack.

We feel a camaraderie with the other families scheduled around us; we know all the kids’ names and cheer them on. It occurs to me this is why people like sports. I’m uncoordinated on land and only want to do things I’m good at, so I never did sports, but it’s satisfying to feel like we’re all working toward the same goal. While not every kid is on the same level, none of the regulars are screaming anymore. They’ve broken through or maybe back: to before they took their first breath and started to cry.

Give or take. There were some extended pauses to accommodate teacher turnover. Nearly all the teachers were college students who needed training.

We did ISR. If you google “survival swim lessons,” you’ll find other similar options.

$825 per kid ($105 to register then $120 per week). Not sure if this is regionally specific. I also found a couple places that offer scholarships.

“what is parenting if not an attempt to rectify past trauma?” This! Thank you for articulating so much I experience(d) as well. I’m imagining us in a parallel universe as mother friends parenting kids at/through same ages. 🩷

I love this! I remember when Beckett first started learning how to swim. It was absolutely terrifying and amazing to watch all at the same time.

My grandparents had a pool and I don’t remember actually “learning” how to swim. In fact, I remember more about the parents just having an afternoon social hour while we (cousins included) just tried NOT to drown. I also distinctly remember somehow watching Jaws way, way, way too early in childhood and being absolutely SURE that a huge great white would eventually chomp me in the deep end!

Beautifully written. ❤️